What do you really want to learn? Just imagine a random menu of classes, everything from acrobatics to zoology, animation to zither playing—what would rise to the top of your list? And what would you scroll past without a second thought?

As someone who teaches and organizes classes, I’ve noticed something: some of the most essential topics are also the ones people are least excited about. You can dress up the titles all you want, but unless you’re one of the rare nerds who gets genuinely fired up about them, it’s hard to drum up enthusiasm for sessions like Consent Is Cool, How to Handle All the Feelings You’d Rather Ignore, or A Thru Z: Archiving Compliance Documents.

Communication, in all its many forms, lands in that same yawn-inducing category. At Exam Essentials, one of the most frequent pieces of feedback we get is confusion about why we spend so much time focusing on how providers communicate with patients.

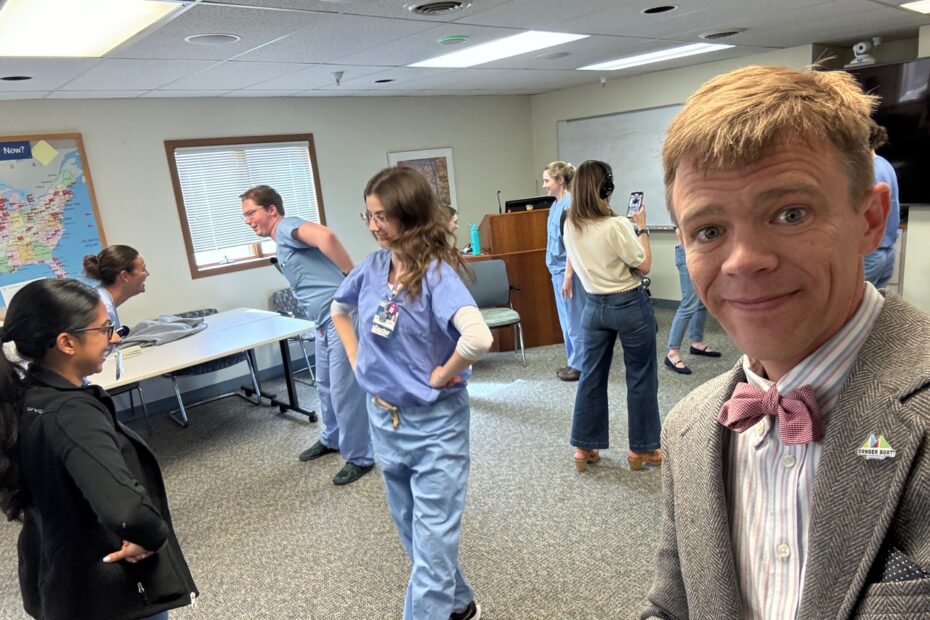

Enter Tane Danger of Danger Boat Productions—yes, Danger is really his last name. He has an answer for this communication conundrum. Improv classes!

From Evening Entertainment to Medical Training

Danger has been teaching improv for two decades. Sometime in the mid-2010s, a colleague invited him to run an improv night for a group of Mayo Clinic associates. What began as a fun evening turned out to have surprising depth. Over time, it became clear that improv wasn’t just helping people unwind—it was helping them communicate better, collaborate more easily, and think more flexibly.

Now, as Artist in Residence at Mayo Clinic through the Dolores Jean Lavins Center for Humanities in Medicine, Danger regularly teaches improv workshops and ongoing classes to residents, departments, and students.

I first learned of his work from a short piece on All Things Considered (it’s worth the three-minute listen). As someone who also teaches communication in healthcare, I was intrigued. I reached out to ask: What exactly makes improv so effective for improving how we connect?

Paying Attention, One Word at a Time

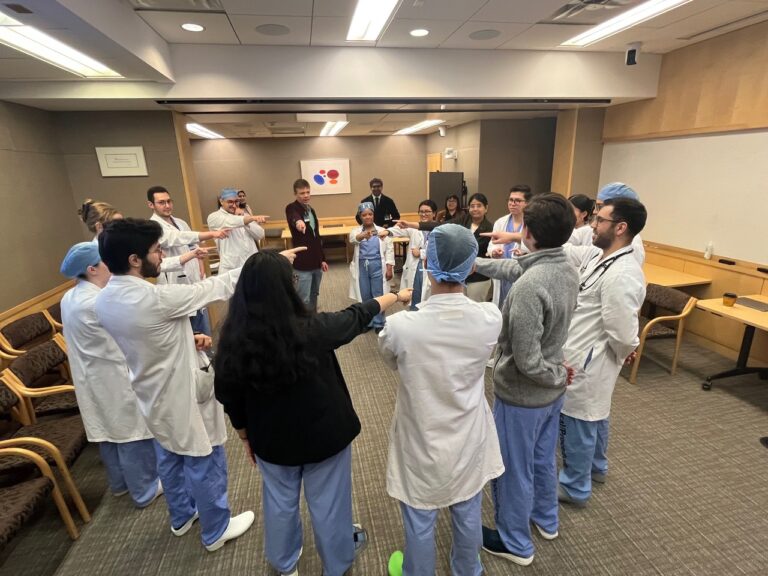

Some lessons from improv are obvious. For example, in an improv game in which someone throws you an invisible ball, you have to pay attention. That’s Communication 101. But the real power of improv runs deeper. It can reshape our concept of the roles between patients and providers.

Danger described an exercise where two people make up a story, each person alternating, offering one word at a time. Afterward, he debriefs participants with questions like:

- How did it feel to only control half the story?

- Did the other person steer the story somewhere you didn’t expect—or didn’t want it to go?

- Did you get stuck?

- Did you find yourself in a pattern of only getting to say the “boring” words while they got the fun ones?

As Danger puts it, “This is what collaboration is all about. It may feel like it’s your job to say ‘and,’ ‘but,’ or ‘the’—boring things over and over again. And yet, if that’s what the story needs, that’s what we have to do.”

He gave this real life context with the example of a patient experiencing a common ailment. A provider might know the diagnosis from reading the chart notes. But going through the motions—asking the patient questions, listening to their answers, responding to concerns—builds trust. Even if it feels repetitive or unnecessary, those “boring words” help the patient feel seen, heard, and safe. You’re giving the ‘story’ what it needs!

The principle here is to not get too attached to where we think a conversation should go because controlling the narrative denies our partner in communication the chance to bring up something they need. Communication is a wide term that includes many concepts. Within that, collaboration — as Danger specified — is a specifically inclusive way to use communication with patients.

Flexibility, Failure, and Letting Go of Perfection

Our conversation helped me understand other ways improv speaks to the needs of people in medicine. It builds skills like flexibility to roll with the unexpected. It helps people get comfortable with ambiguity, which allows us to explore nuance rather than cling to binaries. And it allows us to work against perfectionism and the stress associated with it.

Regarding binaries and perfectionism, Danger was clear: “Yes, in medicine, there are situations where there’s a right and a wrong way. But the more we train our brains to think in binaries—this is good, this is bad, this is right, this is wrong—the harder it becomes to think creatively, face something unfamiliar, or be open to a patient or colleague suggesting a different way of doing things.”

One game he teaches is called Loser Ball. The premise: pass around an imaginary ball—except when the ball comes to you, you DO NOT catch it. Then everyone else applauds you for not catching it. It’s awkward. It feels wrong. That’s the point. Participants come face-to-face with their internal script about how things should go.

That discomfort opens the door to growth: Where did that rule come from? Is it needed? Can I do things differently? And having other people support you as you try something that feels outside your comfort zone helps tremendously.

Reframing the “Too Much Communication” Complaint

Danger helped me reframe something I’ve often wrestled with: the pushback that Exam Essentials spends too much time teaching communication. The truth is, most of us believe we’re already good at it. We’ve been speaking since we were toddlers. We’ve gotten by just fine.

But clinical communication is a different beast. It’s shaped by context, culture, body language, tone, space, power dynamics—and language itself which is constantly shifting. It’s not enough to be competent; we need to be curious, reflective, and adaptable.

In my view, Exam Essentials is just scratching the surface. Danger’s work reaches even deeper. He’s not offering a performance skill—he’s guiding people back to the creativity they already have, and building the confidence to integrate their medical expertise with their personality. For medical professionals, that means bringing their knowledge and training into the room alongside their humanity, humor, and presence.

A Final Note from Danger

Before we ended our conversation, I asked Danger: If he could leave participants with one message, what would it be?

He answered,

"You have everything you need within you to do just about anything you want to do. Improv, at its nature, is getting up on stage, not knowing what’s going to happen, yet knowing that you’re going to make it amazing and fun and beautiful. And that is a really powerful way to operate in the world."

Tane Danger